Sellapan Ramanathan, the sixth President of Singapore. Wikipedia Commons

“Running a government is not like running a church,” shouted S. R. Nathan or Ramanathan, the then Singaporean Ambassador to Washington, who previously served as the head of Singapore’s spook agency under Lee Kwan Yew. (Subsequently, the good ambassador was anointed the 6th President of Singapore and became the longest serving one until 2011).

The year was 1993, and the venue was Van Hise Hall on the beautiful campus of the University of Wisconsin at Madison. The eminent Singaporean was giving a distinguished public lecture at the Center for South East Asian Studies housed at Van Hise.

Only minutes earlier he was painting a rosy picture of Singapore as a great place for American and western investors to do business with its rule of law, efficient bureaucracy, a business-friendly policy climate, … and you get the drift.

When the floor was opened for Q&A, I stood up and pointedly asked the distinguished guest as to why his government was selling military hardware to Myanmar’s State Law and Order Restoration Council, that came to power, after having slaughtered 3,000 unarmed peaceful protesters on the streets of Rangoon and other cities during the nationwide protests in August and September 1988. I had then just started my PhD studies a year before.

That was when the seasoned senior civil servant lost his cool, and went into a tirade against ethics, empathy and morality with his “government-is-NOT-a-church” answer to my question. Scholars of Southeast Asian Studies, young and old, are not so naïve as to expect priestly behavior from state officials and politicians. For the region – created up the United States military command in Asia as a strategic entity during the Second World War – was littered with authoritarian regimes. And many of us lived under or exiled from these places.

But in the age of “corporate social responsibility” – which was becoming fashionable amongst US corporations and western investors, in the 1990’s, thanks to the anti-apartheid divestment movement which had swept across western university campuses and city councils – there was a widespread expectation on American university campuses: that even corporations with their foundational bottom-line logic of profit-above-the-humans – and by extension, political states were expected to draw the moral line as to who they must not do business with – international pariah regimes, murderous, genocidal or officially racist.

So, the Singaporean’s morally repugnant response to a young Burmese graduate student’s morally-loaded question won him no friends amongst Wisconsin’s liberal audience.

Fast-forward to June 2008

I was giving a talk about the same Myanmar military leadership which blocked even the Emergency Humanitarian Aid to 2 million Myanmar victims of Cyclone Nargis which struck the Burmese coastal and delta region just weeks before my visiting lecture at Singapore’s Institute of South East Asian Studies (ISEAS), an organ of the Singaporean state directed and overseen by bankers and senior bureaucrats (see ISEAS Board of Trustees).

My talk was presided over by K. Kesavapany, one of S. R. Nathan’s former subordinates in the Foreign Ministry who was Ambassador-at-large on foreign trade. In attendance was a retired Swiss Ambassador who was on a visiting fellowship. After hearing my talk on the intransigence of Myanmar military leadership, the Swiss gentleman was calling attention to the fact that Singapore was a close business partner of aid-blocking Myanmar military, and openly advocated the need for the city-state to leverage its ties to help ease the humanitarian crisis.

Reminiscent of my exchange with his old boss, the then Ambassador to the United States S. R. Nathan, the seminar’s Singaporean chair went ballistic at the Swiss visiting fellow calling attention to Singapore’s economic leverage with Myanmar generals.

“You of all the people have no right to speak of (Singapore’s) collaboration with Myanmar,” shot back Ambassador Kesavapany, while accusing me of “making a meal” out of his former boss and the then Singapore President Nathan.

It was a fascinating exchange between the two retired diplomats from Singapore and Switzerland.

The Swiss banks (and the Swiss government) live with a lasting blackened image as Nazi-collaborators which gleefully did business with the SS, Hitler’s executioners, who deposited the gold from the victims’ gold teeth and other gold jewelleries melted in the crematorium-gas-chamber complexes of Auschwitz and other death camps. (See from BBC: Nazi gold: Pressure builds on Swiss.)

Particularly poignant about this Swiss-Singaporean exchange I witnessed in a small seminar room at the ISEAS is the ugly parallel between the Swiss and Singaporean model of making profit – which is anything goes, as long as a dime could be squeezed from any situation, genocides or civil wars, illicit trade of drugs or arms.

The blueprint of a typical purpose-built gas-chamber-crematorium complex at Auschwitz-Birkenau, complete with a crucible or a place where metal (gold in this case) was melted, purified and moulded by the SS.

Photo: Maung Zarni, Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial Museum, July 2021.

The remnants of the gas chamber-crematorium complex which the SS dynamited before the Soviet Red Army captured Auschwitz in 1945.

Auschwitz-Birkenau Death Camp, Poland. Photo by Maung Zarni

On Friday 28 October FORSEA hosted a dialogue with the Singaporean scholar and human rights advocate James Gomez (PhD), who directs Asia Centre, to specifically discuss Singapore’s role as the shelter for Myanmar cronies, arms dealers and crooks. Our conversation was precipitated by Bloomberg News’ investigative report on the earliest known Burmese crony, Mr Teza, and how Singapore has provided him and his family with a safe haven in Singapore to arrange different arms deals with Russia, Israel and other unsavoury regimes notorious for selling weapons, openly and below-the-radar.

Singapore’s collaboration with Myanmar’s genocidal regime is decades-old, and encompasses not simply economic and financial, but the area of public relations.

Ex-General Khin Nyunt, the protégé of the late Dictator (General) Ne Win, and head of the Directorate of Defence Services Intelligence in Myanmar, openly told Uzbekistan filmmaker Shahida Tulaganova, in her Al Jazeera documentary about Myanmar genocide of Rohingya, entitled “EXILED” (first, broadcast in 2018).

Ex-General Khin Nyunt interviewed in his residence in Yangon, for EXILED https://filmfreeway.com/EXILED738

In Khin Nyunt’s Burmese words (and my translation): “Oh, Lee Kwan Yew-gyi was so helpful in giving us specific advice as to how to make ourselves more presentable” to the international community.

Khin Nyunt was one of the operational masterminds of the Rohingya genocidal purges which began, as an act of policy, in earnest in February 1978, just as Khmer Rouge genocide was in his final phase.

Singapore’s close commercial and diplomatic collaboration with a mass-murderous regime is not a recent phenomenon, which emerged only in the 1990’s after Myanmar military hit international headlines in the late 1980’s with its blood-bath of civilian protesters calling for the end to dictatorship.

On the contrary, Singapore genocide complicity dates all the way back to Cambodian Genocide (1975-78).

Getting Away With Genocide: Cambodia’s Long Struggle Against the Khmer (Pluto Press, 2004)

In their book Getting Away With Genocide: Cambodia’s Long Struggle Against the Khmer (Pluto Press, 2004), the authors Dr Helen Jarvis and Tom Fawthrop specifically stated the role of ASEAN – the original five members of Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei – in providing political and diplomatic support for Pol Pot’s regime, even after the facts of the latter’s genocide came to light in the 1980’s.

According to these two researchers, US, UK and China seated the Pol Pot regime as the real representative of Cambodian people at the United Nations General Assembly until the early 1990’s. On its part, Singapore was leading the original ASEAN in providing the regional diplomatic support – and public relations campaigns – for Pol Pot.

In response to Dr Gomez’s dialogue with me, Youk Chhang, the Executive Director of the (Genocide) Documentation Center of Cambodia and a Khmer Rouge survivor, emailed me, “Singaporeans were here during Khmer Rouge genocide”. Importantly, he emailed me the DC-Cam’s “Singapore dossier”.

Between May 11 and 16, 1978, an economic delegation from Singapore paid an official visit to Democratic Kampuchea, led by Mr. Lee Chiong Giam, Director of the Economic Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Singapore. From May 12 to 14, 1978, the cadres of the Khmer Rouge Ministry of Foreign Affairs accompanied the delegation from Singapore to visit Angkor Wat, located in Siem Reap province.

(Photo and Caption: Courtesy of Genocide Documentation Center of Cambodia).

It is worth quoting at length from the Singapore Dossier:

“According to commerce records held by the Documentation Center of Cambodia, between 1977 and 1978, there were at least two ships that transported engine oil, automotive spare parts and other goods from Singapore to Kampong Som port on two separate occasions. The total amount of good exchanged in these instances were more than 3,750 tons or around 1, 6 million U.S. dollars.

In 2003, Youk Chhang, Director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia interviewed Van Rith, the former Chief of State for the Commerce Committee of Democratic Kampuchea. During this interview, Rith stated that Democratic Kampuchea had brought a thousand barrels of engine oil from Singapore and stored these in a state warehouse in Phnom Penh. Rith also stated that the Khmer Rouge borrowed 140 Million Yuans or $20 Million U.S. Dollars from China and the Khmer Rouge kept the money in a Chinese bank. At that time the Khmer Rouge paid the Singapore government by way of a Chinese bank.

Hem Lysieng who was a messenger of Launh, the Chief of State for Fishing at Kampong Som, told DC-Cam that Khmer Rouge had sold hundreds of tons of sea produce (e.g., fish, crab, squid, and shrimp) to Singapore through the Kampong Som port. Lysieng added that when the Khmer Rouge returned from fishing, they contacted Singapore, which promptly received the produce at the port. The Khmer Rouge also sent good quality fish, crab, squid, and shrimp to the Khmer Rouge senior leaders at office 870 every week.

After the Khmer Rouge regime collapsed in 1979, Singapore still continued diplomatic ties with the Khmer Rouge. Singapore also supported the Khmer Rouge in their effort to establish a functioning organization and continue their struggle against the People’s Republic of Kampuchea and Vietnamese forces up until the Paris Peace Accord of October 23, 1991.”

Singapore: No moral or ethical advancement

If Singapore under the late Lee Kwan Yew was in bed with the genocidal Khmer Rouge – and held Myanmar generals’ hands – for several decades, Singapore under his son PM Lee Hsien Loong is simply repeating the same genocide indifferent behaviour, while downplaying Singapore’s economic interests in the civil-war-torn Myanmar. (Mothership, Singapore)

Two months after the bloody coup in Myanmar, Singaporean leader had this to say to the BBC Interviewer who asked, “Do economic considerations come before these humanitarian concerns?”

PM Lee: I do not think it is a matter of economic considerations or to benefit from trade from Myanmar. The volume of trade is very small for us and for many other countries. Question is, what can make a difference to them, and if you do impose sanctions, who will hurt? It will not be the military, or the Generals who will hurt. It will be the Myanmar population who will hurt. It will deprive them of food, medicine, essentials, and opportunities for education. How does that make things better?

According to the Reuter’s news report published two months after the 2021 coup, “Singapore had a cumulative $24.1 billion of investments approved as of 2020 since 1988.” And according to Dr Gomez’s Asia Center, many international businesses use the city-state as a conduit to bypass western sanctions and other restrictions regarding doing business in Myanmar. Of the US $442.2 million which Myanmar (military) received as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) after the military coup of February 2021, Singapore is the Number One source at US$297 million.

While morally reprehensible, it is at least understandable that the economically struggling Singapore of Lee Kwan Yew and S. R. Nathan (aka) Ramanathan, in its first decade, felt compelled to make profit out of its export of US$20 million-worth of engine oil (US$120 million at today’s value) to Khmer Rouge in 1977. Here it is instructive to quote from the dossier on Singapore-Khmer Rouge relations compiled by the (Genocide) Documentation Center of Cambodia:

Hem Lysieng who was a messenger of Launh, the Chief of State for Fishing at Kampong Som, told DC-Cam that Khmer Rouge had sold hundreds of tons of sea produce (e.g., fish, crab, squid, and shrimp) to Singapore through the Kampong Som port. Lysieng added that when the Khmer Rouge returned from fishing, they contacted Singapore, which promptly received the produce at the port.

But as measured in state’s conduct regarding the Asian genocidal regimes in its neighbourhood, Singapore has made absolutely no moral or ethical advancement from the founding decade of 1970’s with its per capita GDP of $1,000.00 to the 21st century where it could boast per capita GDP of $54,000.00 in the early decades of the 21st century. (See “Total’s advisers honour Lee Kuan Yew,”)

Besides its existential state ideology of Survival, the Cold War in the late 1970’s freed Singapore of any external ethical or moral principles in its extraction of profits out of Khmer Rouge’s Democratic Republic of Kampuchea. The fact that Khmer Rouge’s Kampuchea was not a member of the Association of South East Asian also helped: Pol Pot’s genocide was never not on the ASEAN’s agenda.

The rich Singapore now proudly considers itself as “First World”, a cut-above-the-rest of Southeast Asia. Yet, it retains its old state conduct of doing business with unsavoury regimes whatever their atrocious crimes or ASEAN membership status.

As a matter of fact, Singapore has further expanded its economic interface with the newly emerging genocidal regime of Myanmar.

By the year 2012 when the late founder Lee Kyan Yew was inducted into the boards of directors and international councils ( for instance, Total Oil Corporation of France and Wall Street’s JP Morgan and Chase) Singapore was treating Myanmar, already an international pariah, not only as an important business partner – $24 billion in investment in resource-rich Myanmar is no small amount, by any standards – but also as a testing ground for the weapons developed in Singapore for global export. (See “Singapore gains toehold in world arms industry”.)

In 2010 Myanmar military hit headlines news with the Democratic Voice of Myanmar’s ground-breaking report on its attempt to develop a nuclear weapons program.

I travelled to Jakarta and Bangkok with Robert Kelly, a leading American weapons engineer with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and former head of the United Nations WMD inspection team in Saddam’s Iraq to speak on Myanmar military leadership.

WMD expert Robert Kelly, formerly of IAEA, speaking on Myanmar’s nuclear weapons program, (on the panel with the author M. Zarni, to the right), Jakarta, October 2010.

In those days, as a Burmese scholar who specializes inter alia Myanmar military’s inner workings, I was tracking down “high value” Burmese military defectors who received advanced training in the Russian Federation for in-depth interviews and debriefings. One of my interviewees was a personal staff officer (or aide-de-camp) with the rank of a major to the head of the Procurement Division in the Myanmar Ministry of Defence revealed that Singapore had an arrangement with the Myanmar regime whereby it would ship its newly developed weapons to Myanmar for testing, would shoot promotional videos for international arms markets and gift the newly tested weapons to the host – Myanmar Ministry of Defence.

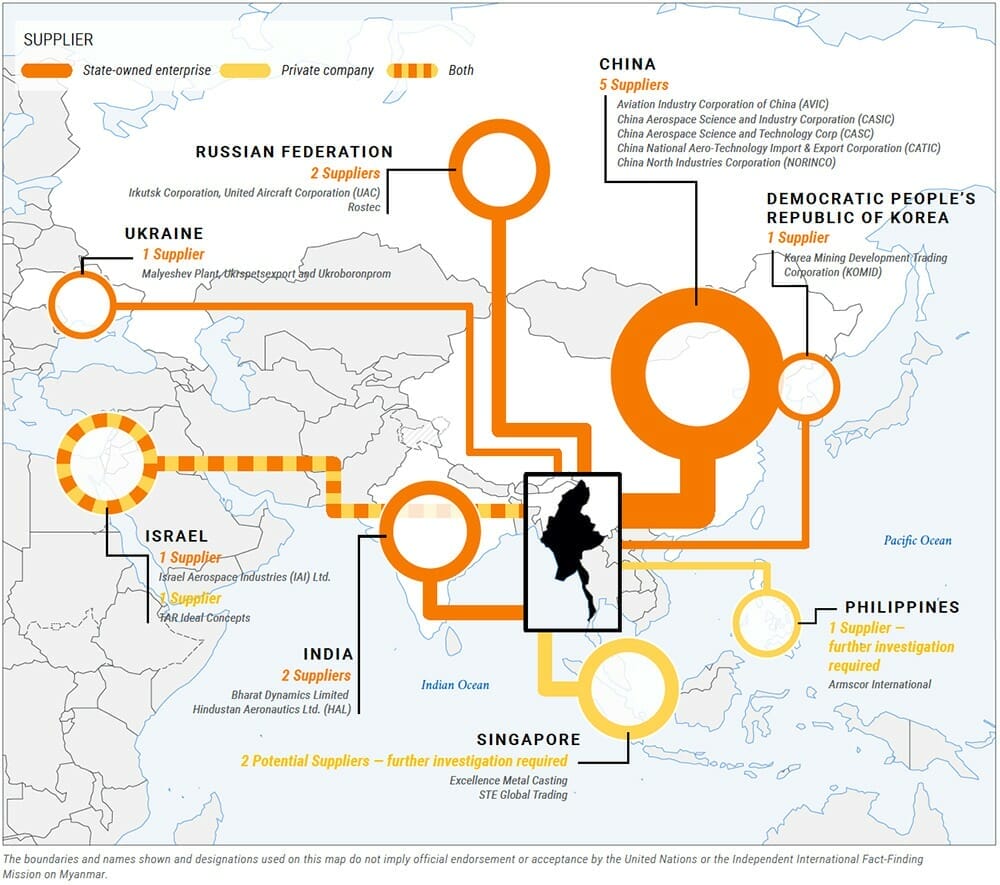

In the infographic published by the United Nations Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar or UNFFM (dated August 2019, which officially blew the genocide whistle, named Singapore alongside Russian Federation, Israel, China, India, N. Korea (DPRK), it showed Ukraine and the Philippines as a major source of weapons for the Myanmar military. By then the Myanmar military was accused of committing a textbook genocide against Rohingyas in Western Myanmar by credible international human rights watchdogs and academic institutions (including FFM itself).

In August 2022, Justice for Myanmar, a highly regarded activist research network specializing in the economic and financial aspects of Myanmar military issued a well-researched report where a staggering number of Singapore-based subsidiary or associated companies – 38 out of a total of 78 companies – which had brokered arms and equipment to the Myanmar Ministry of Defence since Myanmar’s genocide had come to light in 2017.

Its report stresses that “Singapore has long been a known financial and trade hub for the Myanmar military’s arms procurement and this poses an imminent threat to the lives of millions of Myanmar people.” (see “Exposed: Companies Brokering Arms Equipment to Myanmar Military“.) Indeed, Myanmar military has been using its weapons to destroy religious and ethnic minorities, as well as pro-human rights activists throughout the country.

In response to the latest war crime by Myanmar Air Force – that is, air strikes on the civilian concert in the ethnic minority state of Kachin on 23 October 2022 – Minister for Foreign Affairs Dr Vivian Balakrishnan issued the following spin:

“The Foreign Ministers discussed the situation in Myanmar and expressed deep regret over the loss of lives from the recent airstrikes in Kachin State. Minister Balakrishnan reiterated Singapore’s deep disappointment at the lack of progress in the implementation of the Five-Point Consensus, the escalation of violence and the worsening situation on the ground.”

When it comes to official crocodile’s tears, the Singapore Government appears to simply cut and paste from its previous media statements. Reuters news report – dated 31 March 2021 – did not fail to notice this rather despicable act: “the framing of Singapore’s initial response to the coup was word for word the same as for Thailand’s in 2014: “Singapore expresses grave concern… we hope that the situation will return to normal as soon as possible.””

Dr James Gomez, Asia Centre

I put it to my FORSEA Dialogue guest, the Singaporean-born scholar and rights advocate Dr James Gomez, “why do you think Singapore is making noises about Myanmar’s violence and rights violations while continuing to keep their massive investment – by any standards – in Myanmar?”

His succinct reply: “Singapore is fork-tongued, (as you know).”

Obviously, Singaporean leaders – from the late LKY to his successor-son Lee Hsien Loong – and Singaporeans in general – are rightly proud of their metamorphosis from “The Third World to First.”

As one steps out of the terminals at London’s Heathrow International Airport, one notices that Singaporean passport enjoys the no-UK-visa-required status alongside Canada, Switzerland, Norway, EU, Australia and Japan. That’s no small feat for a tiny city-state with little or no natural or adequate human resources. Roughly 200,000 skilled and semi-skilled migrant workers from Myanmar alone live and work in Singapore, alongside other Asians from Indonesia, the Philippines, China, Indian, etc., as well as Israeli weapons engineers, European and N. American academics and businessmen and -women.

From Third World to First: The Singapore Story: 1965-2000

Lee Kuan Yew, Henry Kissinger (Foreword by)

But Singapore’s riches and its founder Lee Kwan Yew’s coveted “First World” status have been built inter alia on the millions of corpses of fellow Asians, who have perished in the hands of Khmer Rouge and Myanmar military regimes over the last 50-years.

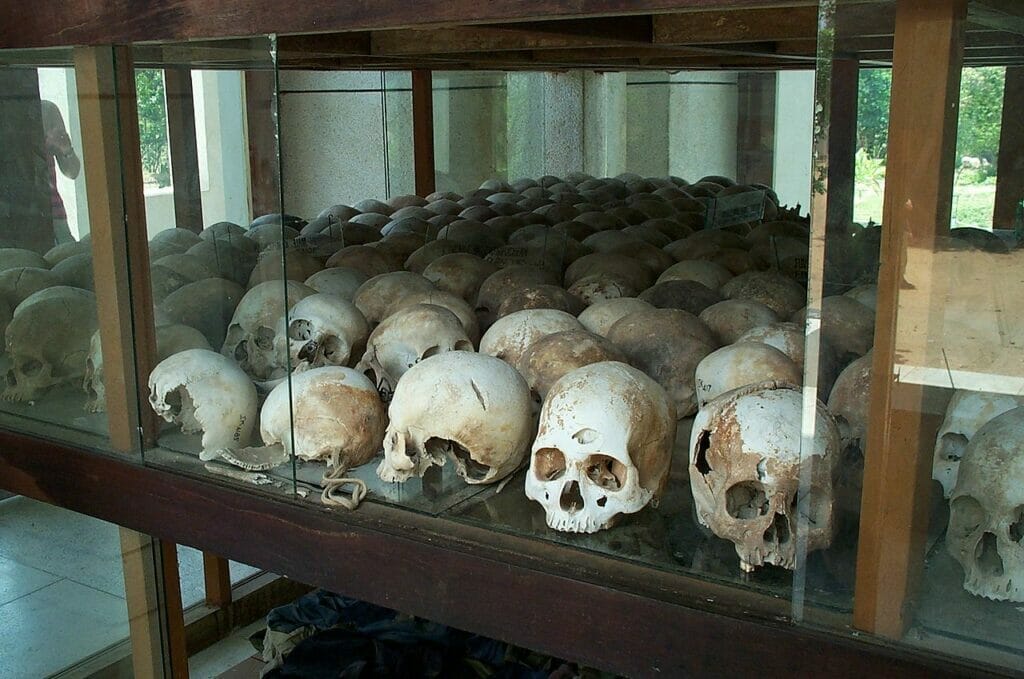

Skulls of Khmer Rouge victims on display at Choeung Ek genocidal memorial museum in Phnom Penh. Wikipedia Commons

A few years ago, I led a small delegation of international lawyers and noted genocide scholars, including Gregory Stanton, founding president of Genocide Watch and a pioneering researcher on the Khmer Rouge genocide, to Kuala Lumpur where we met with the Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah and discussed practical ways in which the Malaysian Government could help advance international accountability on the crimes perpetrated by one of ASEAN members, specifically the genocide of Rohingyas. At a private dinner which the Foreign Minister hosted for us in Putrajaya, Malaysia’s administrative capital, I asked him why Malaysian government was open to helping activists and lawyers to seek justice for the genocide victims in Myanmar.

He answered, “we failed in Cambodia. We don’t want to repeat the past.”

Alas, no such enlightened words of acknowledgement or forward-looking policy wisdom from his Singaporean counterparts.

Singapore certainly possesses “First World” Wealth, but it tragically lacks “First World” ethics.

To belabour the obvious, running a government is not like running a church, as the 6th President, the late S. R. Nathan, angrily shouted at me some 30 years ago. But running a state should not mean collaborating and profiting from the genocidal regimes in the backyard.

Maung Zarni